- Details

- Written by Super User

- Category: Rome

- Hits: 3140

Pantheon, Rome

|

|

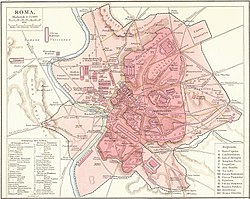

The location of the church today

Click on the map to see marker. |

|

| Location | Regio IX Circus Flaminius |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41.8986°N 12.4768°E |

| Type | Roman temple |

| History | |

| Builder | Trajan, Hadrian |

| Founded | 113–125 AD (current building) |

The Pantheon (UK: /ˈpænθiən/, US: /-ɒn/;[1] Latin: Pantheum,[nb 1] from Greek Πάνθειον Pantheion, "[temple] of all the gods") is a former Roman temple and since the year 609 a Catholic church (Basilica di Santa Maria ad Martyres or Basilica of St. Mary and the Martyrs), in Rome, Italy, on the site of an earlier temple commissioned by Marcus Agrippa during the reign of Augustus (27 BC – 14 AD). It was rebuilt by the emperor Hadrian and probably dedicated c. 126 AD. Its date of construction is uncertain, because Hadrian chose not to inscribe the new temple but rather to retain the inscription of Agrippa's older temple, which had burned down.[2]

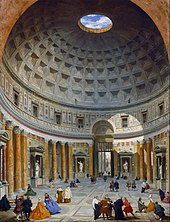

The building is cylindrical with a portico of large granite Corinthian columns (eight in the first rank and two groups of four behind) under a pediment. A rectangular vestibule links the porch to the rotunda, which is under a coffered concrete dome, with a central opening (oculus) to the sky. Almost two thousand years after it was built, the Pantheon's dome is still the world's largest unreinforced concrete dome.[3] The height to the oculus and the diameter of the interior circle are the same, 43 metres (142 ft).[4]

It is one of the best-preserved of all Ancient Roman buildings, in large part because it has been in continuous use throughout its history and, since the 7th century, the Pantheon has been in use as a church dedicated to "St. Mary and the Martyrs" (Latin: Sancta Maria ad Martyres) but informally known as "Santa Maria Rotonda".[5] The square in front of the Pantheon is called Piazza della Rotonda. The Pantheon is a state property, managed by Italy's Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism through the Polo Museale del Lazio. In 2013, it was visited by over 6 million people.

The Pantheon's large circular domed cella, with a conventional temple portico front, was unique in Roman architecture. Nevertheless, it became a standard exemplar when classical styles were revived, and has been copied many times by later architects.[6]

Contents

Etymology

The name "Pantheon" is from the Ancient Greek "Pantheion" (Πάνθειον) meaning "of, relating to, or common to all the gods": (pan- / "παν-" meaning "all" + theion / "θεῖον"= meaning "of or sacred to a god").[7] Cassius Dio, a Roman senator who wrote in Greek, speculated that the name comes either from the statues of many gods placed around this building, or from the resemblance of the dome to the heavens.[8] His uncertainty strongly suggests that "Pantheon" (or Pantheum) was merely a nickname, not the formal name of the building.[9] In fact, the concept of a pantheon dedicated to all the gods is questionable. The only definite pantheon recorded earlier than Agrippa's was at Antioch in Syria, though it is only mentioned by a sixth-century source.[10] Ziegler tried to collect evidence of pantheons, but his list consists of simple dedications "to all the gods" or "to the Twelve Gods", which are not necessarily true pantheons in the sense of a temple housing a cult that literally worships all the gods.[11]

Godfrey and Hemsoll point out that ancient authors never refer to Hadrian's Pantheon with the word aedes, as they do with other temples, and the Severan inscription carved on the architrave uses simply "Pantheum," not "Aedes Panthei" (temple of all the gods).[12] It seems highly significant that Dio does not quote the simplest explanation for the name—that the Pantheon was dedicated to all the gods.[13] In fact, Livy wrote that it had been decreed that temple buildings (or perhaps temple cellae) should only be dedicated to single divinities, so that it would be clear who would be offended if, for example, the building were struck by lightning, and because it was only appropriate to offer sacrifice to a specific deity (27.25.7–10).[14] Godfrey and Hemsoll maintain that the word Pantheon "need not denote a particular group of gods, or, indeed, even all the gods, since it could well have had other meanings. ... Certainly the word pantheus or pantheos, could be applicable to individual deities. ... Bearing in mind also that the Greek word θεῖος (theios) need not mean 'of a god' but could mean 'superhuman', or even 'excellent'."[12]

Since the French Revolution, when the church of Sainte-Geneviève in Paris was deconsecrated and turned into the secular monument called the Panthéon of Paris, the generic term pantheon has sometimes been applied to other buildings in which illustrious dead are honoured or buried.[1]

History

Ancient

In the aftermath of the Battle of Actium (31 BC), Marcus Agrippa started an impressive building program: the Pantheon was a part of the complex created by him on his own property in the Campus Martius in 29–19 BC, which included three buildings aligned from south to north: the Baths of Agrippa, the Basilica of Neptune, and the Pantheon.[15] It seems likely that the Pantheon and the Basilica of Neptune were Agrippa's sacra privata, not aedes publicae (public temples).[16] The former would help explain how the building could have so easily lost its original name and purpose (Ziolkowski contends that it was originally the Temple of Mars in Campo)[17] in such a relatively short period of time.[18]

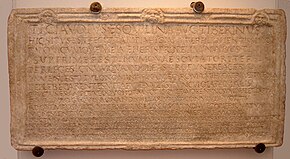

It had long been thought that the current building was built by Agrippa, with later alterations undertaken, and this was in part because of the Latin inscription on the front of the temple[19] which reads:

- M·AGRIPPA·L·F·COS·TERTIVM·FECIT

or in full, "M[arcus] Agrippa L[ucii] f[ilius] co[n]s[ul] tertium fecit," meaning "Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, made [this building] when consul for the third time."[20] However, archaeological excavations have shown that the Pantheon of Agrippa had been completely destroyed except for the façade. Lise Hetland argues that the present construction began in 114, under Trajan, four years after it was destroyed by fire for the second time (Oros. 7.12). She reexamined Herbert Bloch's 1959 paper, which is responsible for the commonly maintained Hadrianic date, and maintains that he should not have excluded all of the Trajanic-era bricks from his brick-stamp study. Her argument is particularly interesting in light of Heilmeyer's argument that, based on stylistic evidence, Apollodorus of Damascus, Trajan's architect, was the obvious architect.[21]

The form of Agrippa's Pantheon is debated. As a result of excavations in the late 19th century, archaeologist Rodolfo Lanciani concluded that Agrippa's Pantheon was oriented so that it faced south, in contrast with the current layout that faces north, and that it had a shortened T-shaped plan with the entrance at the base of the "T". This description was widely accepted until the late 20th century. While more recent archaeological diggings have suggested that Agrippa's building might have had a circular form with a triangular porch, and it might have also faced north, much like the later rebuildings, Ziolkowski complains that their conclusions were based entirely on surmise; according to him, they did not find any new datable material, yet they attributed everything they found to the Agrippan phase, failing to account for the fact that Domitian, known for his enthusiasm for building and known to have restored the Pantheon after 80 AD, might well have been responsible for everything they found. Ziolkowski argues that Lanciani's initial assessment is still supported by all of the finds to date, including theirs; furthermore he expresses skepticism because the building they describe, "a single building composed of a huge pronaos and a circular cella of the same diameter, linked by a relatively narrow and very short passage (much thinner than the current intermediate block), has no known parallels in classical architecture and would go against everything we know of Roman design principles in general and of Augustan architecture in particular."[22]

The only passages referring to the decoration of the Agrippan Pantheon written by an eyewitness are in Pliny the Elder's Natural History. From him we know that "the capitals, too, of the pillars, which were placed by M. Agrippa in the Pantheon, are made of Syracusan bronze",[23] that "the Pantheon of Agrippa has been decorated by Diogenes of Athens, and the Caryatides, by him, which form the columns of that temple, are looked upon as masterpieces of excellence: the same, too, with the statues that are placed upon the roof,"[24] and that one of Cleopatra's pearls was cut in half so that each half "might serve as pendants for the ears of Venus, in the Pantheon at Rome".[25]

The Augustan Pantheon was destroyed along with other buildings in a huge fire in the year 80 AD. Domitian rebuilt the Pantheon, which was burnt again in 110 AD.[26]

The degree to which the decorative scheme should be credited to Hadrian's architects is uncertain. Finished by Hadrian but not claimed as one of his works, it used the text of the original inscription on the new façade (a common practice in Hadrian's rebuilding projects all over Rome; the only building on which Hadrian put his own name was the Temple to the Deified Trajan).[27] How the building was actually used is not known. The Historia Augusta says that Hadrian dedicated the Pantheon (among other buildings) in the name of the original builder (Hadr. 19.10), but the current inscription could not be a copy of the original; it provides no information as to who Agrippa's foundation was dedicated to, and, in Ziolkowski's opinion, it was highly unlikely that in 25 BC Agrippa would have presented himself as "consul tertium." On coins, the same words, "M. Agrippa L.f cos. tertium", were the ones used to refer to him after his death; consul tertium serving as "a sort of posthumous cognomen ex virtute, a remembrance of the fact that, of all the men of his generation apart from Augustus himself, he was the only one to hold the consulship thrice."[28] Whatever the cause of the alteration of the inscription might have been, the new inscription reflects the fact that there was a change in the building's purpose.[29]

Cassius Dio, a Graeco-Roman senator, consul and author of a comprehensive History of Rome, writing approximately 75 years after the Pantheon's reconstruction, mistakenly attributed the domed building to Agrippa rather than Hadrian. Dio appears to be the only near-contemporaneous writer to mention the Pantheon. Even by the year 200, there was uncertainty about the origin of the building and its purpose:

Agrippa finished the construction of the building called the Pantheon. It has this name, perhaps because it received among the images which decorated it the statues of many gods, including Mars and Venus; but my own opinion of the name is that, because of its vaulted roof, it resembles the heavens.

— Cassius Dio History of Rome 53.27.2

In 202, the building was repaired by the joint emperors Septimius Severus and his son Caracalla (fully Marcus Aurelius Antoninus), for which there is another, smaller inscription on the architrave of the façade, under the aforementioned larger text.[30][31] This now-barely legible inscription reads:

- IMP · CAES · L · SEPTIMIVS · SEVERVS · PIVS · PERTINAX · ARABICVS · ADIABENICVS · PARTHICVS · MAXIMVS · PONTIF · MAX · TRIB · POTEST · X · IMP · XI · COS · III · P · P · PROCOS ET

- IMP · CAES · M · AVRELIVS · ANTONINVS · PIVS · FELIX · AVG · TRIB · POTEST · V · COS · PROCOS · PANTHEVM · VETVSTATE · CORRVPTVM · CVM · OMNI · CVLTV · RESTITVERVNT

In English, this means:

- Emp[eror] Caes[ar] L[ucius] Septimius Severus Pius Pertinax, victorious in Arabia, victor of Adiabene, the greatest victor in Parthia, Pontif[ex] Max[imus], 10 times tribune, 11 times proclaimed emperor, three times consul, P[ater] P[atriae], proconsul, and

- Emp[eror] Caes[ar] M[arcus] Aurelius Antoninus Pius Felix Aug[ustus], five times tribune, consul, proconsul, have carefully restored the Pantheon ruined by age.[32]

Medieval

In 609, the Byzantine emperor Phocas gave the building to Pope Boniface IV, who converted it into a Christian church and consecrated it to St. Mary and the Martyrs on 13 May 609: "Another Pope, Boniface, asked the same [Emperor Phocas, in Constantinople] to order that in the old temple called the Pantheon, after the pagan filth was removed, a church should be made, to the holy virgin Mary and all the martyrs, so that the commemoration of the saints would take place henceforth where not gods but demons were formerly worshipped."[33] Twenty-eight cartloads of holy relics of martyrs were said to have been removed from the catacombs and placed in a porphyry basin beneath the high altar.[34] On its consecration, Boniface placed an icon of the Mother of God as 'Panagia Hodegetria' (All Holy Directress) within the new sanctuary.[35]

The building's consecration as a church saved it from the abandonment, destruction, and the worst of the spoliation that befell the majority of ancient Rome's buildings during the early medieval period. However, Paul the Deacon records the spoliation of the building by the Emperor Constans II, who visited Rome in July 663:

Remaining at Rome twelve days he pulled down everything that in ancient times had been made of metal for the ornament of the city, to such an extent that he even stripped off the roof of the church [of the blessed Mary], which at one time was called the Pantheon, and had been founded in honour of all the gods and was now by the consent of the former rulers the place of all the martyrs; and he took away from there the bronze tiles and sent them with all the other ornaments to Constantinople.

Much fine external marble has been removed over the centuries – for example, capitals from some of the pilasters are in the British Museum.[36] Two columns were swallowed up in the medieval buildings that abutted the Pantheon on the east and were lost. In the early 17th century, Urban VIII Barberini tore away the bronze ceiling of the portico, and replaced the medieval campanile with the famous twin towers (often wrongly attributed to Bernini[37]) called "the ass's ears",[38] which were not removed until the late 19th century.[39] The only other loss has been the external sculptures, which adorned the pediment above Agrippa's inscription. The marble interior has largely survived, although with extensive restoration.

Renaissance

Since the Renaissance the Pantheon has been the site of several important burials. Among those buried there are the painters Raphael and Annibale Carracci, the composer Arcangelo Corelli, and the architect Baldassare Peruzzi. In the 15th century, the Pantheon was adorned with paintings: the best-known is the Annunciation by Melozzo da Forlì. Filippo Brunelleschi, among other architects, looked to the Pantheon as inspiration for their works.

Pope Urban VIII (1623 to 1644) ordered the bronze ceiling of the Pantheon's portico melted down. Most of the bronze was used to make bombards for the fortification of Castel Sant'Angelo, with the remaining amount used by the Apostolic Camera for various other works. It is also said that the bronze was used by Bernini in creating his famous baldachin above the high altar of St. Peter's Basilica, but, according to at least one expert, the Pope's accounts state that about 90% of the bronze was used for the cannon, and that the bronze for the baldachin came from Venice.[41] Concerning this, an anonymous contemporary Roman satirist quipped in a pasquinade (a publicly posted poem) that quod non fecerunt barbari fecerunt Barberini ("What the barbarians did not do the Barberinis [Urban VIII's family name] did").

In 1747, the broad frieze below the dome with its false windows was "restored," but bore little resemblance to the original. In the early decades of the 20th century, a piece of the original, as could be reconstructed from Renaissance drawings and paintings, was recreated in one of the panels.[citation needed]

Modern

Two kings of Italy are buried in the Pantheon: Vittorio Emanuele II and Umberto I, as well as Umberto's Queen, Margherita. It was supposed to be the final resting place for the Monarchs of Italy of House of Savoy, but the Monarchy was abolished in 1946 and the republican authorities have refused to grant burial to the former kings who died in exile (Victor Emmanuel III and Umberto II). The Organization of the National Institute for the Honour Guard of the Royal Tombs of the Pantheon, which mounts guards of honour at the royal tombs of the Pantheon, was originally chartered by the House of Savoy and subsequently operating with authorization of the Italian Republic, mounts as guards of honour in front of the royal tombs.[citation needed]

The Pantheon is in use as a Catholic church, and as such, visitors are asked to keep an appropriate level of deference. Masses are celebrated there on Sundays and holy days of obligation. Weddings are also held there from time to time.

Cardinal deaconry

On 23 July 1725, the Pantheon was established as Cardinal-deaconry of S. Maria ad Martyres, i.e. a titular church for a cardinal-deacon.

On 26 May 1929, this deaconry was suppressed to establish the Cardinal Deaconry of S. Apollinare alle Terme Neroniane-Alessandrine.[citation needed]

Structure

Portico

The building was originally approached by a flight of steps. Later construction raised the level of the ground leading to the portico, eliminating these steps.[5]

The pediment was decorated with relief sculpture, probably of gilded bronze. Holes marking the location of clamps that held the sculpture suggest that its design was likely an eagle within a wreath; ribbons extended from the wreath into the corners of the pediment.[42]

On the intermediate block between the portico and the rotunda, the remains of a second pediment suggests that existing portico is much shorter than originally intended. A portico aligned with the second pediment would fit columns with shafts 50 Roman feet (14.8 metres) tall and capitals 10 Roman feet tall (3 metres), whereas the existing portico has shafts 40 Roman feet (11.9 metres) tall and capitals eight Roman feet (2.4 metres) tall.[43][44]

Mark Wilson Jones has attempted to explain the design adjustments by suggesting that, once the higher pediment had been constructed, the required 50 foot columns failed to arrive (possibly as a result of logistical difficulties).[43] The builders then had to make some awkward adjustments to fit the shorter columns and pediments. Rabun Taylor has noted that, even if the taller columns were delivered, basic construction constraints may have prevented their use.[44] Assuming that each column would first be laid on the floor next to its pediment before being pivoted upright (using something like an A-frame), there would be a space requirement of a column-length on one side of the pediment, and at least a column-length on the opposite side for the pivoting equipment and ropes. With 50 foot columns “there was no way to sequence the erection of [the columns] without creating a hopeless snarl. The shafts were simply too long to be positioned on the floor in a workable configuration, regardless of sequence.”[44] Specifically, the innermost row of columns would be blocked by the main body of the temple, and in the later stages of construction some already-erected columns would inevitably obstruct the erection of further columns.

However, it has also been argued that the scale of the portico was related to the urban design of the space in front of the temple.[45]

The grey granite columns that were actually used in the Pantheon's pronaos were quarried in Egypt at Mons Claudianus in the eastern mountains. Each was 11.9 metres (39 ft) tall, 1.5 metres (4 ft 11 in) in diameter, and 60 tonnes (59 long tons; 66 short tons) in weight.[46] These were dragged more than 100 km (62 miles) from the quarry to the river on wooden sledges. They were floated by barge down the Nile River when the water level was high during the spring floods, and then transferred to vessels to cross the Mediterranean Sea to the Roman port of Ostia. There, they were transferred back onto barges and pulled up the Tiber River to Rome.[47] After being unloaded near the Mausoleum of Augustus, the site of the Pantheon was still about 700 metres away.[48] Thus, it was necessary to either drag them or to move them on rollers to the construction site.

In the walls at the back of the Pantheon's portico are two huge niches, perhaps intended for statues of Augustus Caesar and Agrippa.

The large bronze doors to the cella, measuring 4.45 metres (14.6 ft) wide by 7.53 metres (24.7 ft) high, are the oldest in Rome.[49] These were thought to be a 15th-century replacement for the original, mainly because they were deemed by contemporary architects to be too small for the door frames.[50] However, analysis of the fusion technique confirmed that these are the original Roman doors,[49] a rare example of Roman monumental bronze surviving, despite cleaning and the application of Christian motifs over the centuries.

Rotunda

The 4,535-tonne (4,463-long-ton; 4,999-short-ton) weight of the Roman concrete dome is concentrated on a ring of voussoirs 9.1 metres (30 ft) in diameter that form the oculus, while the downward thrust of the dome is carried by eight barrel vaults in the 6.4-metre-thick (21 ft) drum wall into eight piers. The thickness of the dome varies from 6.4 metres (21 ft) at the base of the dome to 1.2 metres (3.9 ft) around the oculus.[51] The materials used in the concrete of the dome also vary. At its thickest point, the aggregate is travertine, then terracotta tiles, then at the very top, tufa and pumice, both porous light stones. At the very top, where the dome would be at its weakest and vulnerable to collapse, the oculus lightens the load.[52]

No tensile test results are available on the concrete used in the Pantheon; however, Cowan discussed tests on ancient concrete from Roman ruins in Libya, which gave a compressive strength of 20 MPa (2,900 psi). An empirical relationship gives a tensile strength of 1.47 MPa (213 psi) for this specimen.[51] Finite element analysis of the structure by Mark and Hutchison[53] found a maximum tensile stress of only 0.128 MPa (18.5 psi) at the point where the dome joins the raised outer wall.[3]

The stresses in the dome were found to be substantially reduced by the use of successively less dense aggregate stones, such as small pots or pieces of pumice, in higher layers of the dome. Mark and Hutchison estimated that, if normal weight concrete had been used throughout, the stresses in the arch would have been some 80% greater. Hidden chambers engineered within the rotunda form a sophisticated structural system.[54] This reduced the weight of the roof, as did the oculus eliminating the apex.[55]

The top of the rotunda wall features a series of brick relieving arches, visible on the outside and built into the mass of the brickwork. The Pantheon is full of such devices – for example, there are relieving arches over the recesses inside – but all these arches were hidden by marble facing on the interior and possibly by stone revetment or stucco on the exterior.

The height to the oculus and the diameter of the interior circle are the same, 43.3 metres (142 ft), so the whole interior would fit exactly within a cube (or, a 43.3-m sphere could fit within the interior).[56] These dimensions make more sense when expressed in ancient Roman units of measurement: The dome spans 150 Roman feet; the oculus is 30 Roman feet in diameter; the doorway is 40 Roman feet high.[57] The Pantheon still holds the record for the world's largest unreinforced concrete dome. It is also substantially larger than earlier domes.[58] It is the only masonry dome to not require reinforcement. All other extant ancient domes were either designed with tie-rods, chains and banding or have been retrofitted with such devices to prevent collapse.[59]

Though often drawn as a free-standing building, there was a building at its rear which abutted it. While this building helped buttress the rotunda, there was no interior passage from one to the other.[60]

Interior

| External video | |

|---|---|

|

|

Upon entry, visitors are greeted by an enormous rounded room covered by the dome. The oculus at the top of the dome was never covered, allowing rainfall through the ceiling and onto the floor. Because of this, the interior floor is equipped with drains and has been built with an incline of about 30 centimetres (12 in) to promote water runoff.[61][62]

The interior of the dome was possibly intended to symbolize the arched vault of the heavens.[56] The oculus at the dome's apex and the entry door are the only natural sources of light in the interior. Throughout the day, light from the oculus moves around this space in a reverse sundial effect: marking time with light rather than shadow.[63] The oculus also offers cooling and ventilation; during storms, a drainage system below the floor handles rain falling through the oculus.

The dome features sunken panels (coffers), in five rings of 28. This evenly spaced layout was difficult to achieve and, it is presumed, had symbolic meaning, either numerical, geometric, or lunar.[64][65] In antiquity, the coffers may have contained bronze rosettes symbolising the starry firmament.[66]

Circles and squares form the unifying theme of the interior design. The checkerboard floor pattern contrasts with the concentric circles of square coffers in the dome. Each zone of the interior, from floor to ceiling, is subdivided according to a different scheme. As a result, the interior decorative zones do not line up. The overall effect is immediate viewer orientation according to the major axis of the building, even though the cylindrical space topped by a hemispherical dome is inherently ambiguous. This discordance has not always been appreciated, and the attic level was redone according to Neoclassical taste in the 18th century.[67]

Catholic additions

| Church of St. Mary of the Martyrs | |

|---|---|

|

Chiesa Santa Maria dei Martiri

Sancta Maria ad Martyres |

|

The tomb of Raphael

|

|

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Roman Catholic |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Minor basilica, Rectory church |

| Leadership | Msgr. Daniele Micheletti |

| Year consecrated | 13 May 609 |

| Location | |

| Location | Rome, Italy |

| Geographic coordinates | 41.8986°N 12.4768°ECoordinates: 41.8986°N 12.4768°E |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Roman |

| Completed | 126 |

| Specifications | |

| Direction of façade | North |

| Length | 84 metres (276 ft) |

| Width | 58 metres (190 ft) |

| Height (max) | 58 metres (190 ft) |

| Website | |

| Official website | |

The present high altars and the apses were commissioned by Pope Clement XI (1700–1721) and designed by Alessandro Specchi. Enshrined on the apse above the high altar is a 7th-century Byzantine icon of the Virgin and Child, given by Phocas to Pope Boniface IV on the occasion of the dedication of the Pantheon for Christian worship on 13 May 609. The choir was added in 1840, and was designed by Luigi Poletti.

The first niche to the right of the entrance holds a Madonna of the Girdle and St Nicholas of Bari (1686) painted by an unknown artist. The first chapel on the right, the Chapel of the Annunciation, has a fresco of the Annunciation attributed to Melozzo da Forlì. On the left side is a canvas by Clement Maioli of St Lawrence and St Agnes (1645–1650). On the right wall is the Incredulity of St Thomas (1633) by Pietro Paolo Bonzi.

The second niche has a 15th-century fresco of the Tuscan school, depicting the Coronation of the Virgin. In the second chapel is the tomb of King Victor Emmanuel II (died 1878). It was originally dedicated to the Holy Spirit. A competition was held to decide which architect should design it. Giuseppe Sacconi participated, but lost – he would later design the tomb of Umberto I in the opposite chapel.

Manfredo Manfredi won the competition, and started work in 1885. The tomb consists of a large bronze plaque surmounted by a Roman eagle and the arms of the house of Savoy. The golden lamp above the tomb burns in honor of Victor Emmanuel III, who died in exile in 1947.

The third niche has a sculpture by Il Lorenzone of St Anne and the Blessed Virgin. In the third chapel is a 15th-century painting of the Umbrian school, The Madonna of Mercy between St Francis and St John the Baptist. It is also known as the Madonna of the Railing, because it originally hung in the niche on the left-hand side of the portico, where it was protected by a railing. It was moved to the Chapel of the Annunciation, and then to its present position sometime after 1837. The bronze epigram commemorated Pope Clement XI's restoration of the sanctuary. On the right wall is the canvas Emperor Phocas presenting the Pantheon to Pope Boniface IV (1750) by an unknown. There are three memorial plaques in the floor, one conmmemorating a Gismonda written in the vernacular. The final niche on the right side has a statue of St. Anastasius (Sant'Anastasio) (1725) by Bernardino Cametti.[68]

On the first niche to the left of the entrance is an Assumption (1638) by Andrea Camassei. The first chapel on the left, the Chapel of St Joseph in the Holy Land, is the chapel of the Confraternity of the Virtuosi al Pantheon, a confraternity of artists and musicians formed by a 16th-century canon, Desiderio da Segni, to ensure that worship was maintained in the chapel.

The first members were, among others, Antonio da Sangallo the younger, Jacopo Meneghino, Giovanni Mangone, Zuccari, Domenico Beccafumi, and Flaminio Vacca. The confraternity continued to draw members from the elite of Rome's artists and architects, and among later members we find Bernini, Cortona, Algardi, and many others. The institution still exists, and is now called the Academia Ponteficia di Belle Arti (The Pontifical Academy of Fine Arts), based in the palace of the Cancelleria. The altar in the chapel is covered with false marble. On the altar is a statue of St Joseph and the Holy Child by Vincenzo de' Rossi.

To the sides are paintings (1661) by Francesco Cozza, one of the Virtuosi: Adoration of the Shepherds on left side and Adoration of the Magi on right. The stucco relief on the left, Dream of St Joseph, is by Paolo Benaglia, and the one on the right, Rest during the flight from Egypt, is by Carlo Monaldi. On the vault are several 17th-century canvases, from left to right: Cumean Sibyl by Ludovico Gimignani; Moses by Francesco Rosa; Eternal Father by Giovanni Peruzzini; David by Luigi Garzi; and Eritrean Sibyl by Giovanni Andrea Carlone.

The second niche has a statue of St Agnes, by Vincenzo Felici. The bust on the left is a portrait of Baldassare Peruzzi, derived from a plaster portrait by Giovanni Duprè. The tomb of King Umberto I and his wife Margherita di Savoia is in the next chapel. The chapel was originally dedicated to St Michael the Archangel, and then to St. Thomas the Apostle. The present design is by Giuseppe Sacconi, completed after his death by his pupil Guido Cirilli. The tomb consists of a slab of alabaster mounted in gilded bronze. The frieze has allegorical representations of Generosity, by Eugenio Maccagnani, and Munificence, by Arnaldo Zocchi. The royal tombs are maintained by the National Institute of Honour Guards to the Royal Tombs, founded in 1878. They also organize picket guards at the tombs. The altar with the royal arms is by Cirilli.

The third niche holds the mortal remains – his Ossa et cineres, "Bones and ashes", as the inscription on the sarcophagus says – of the great artist Raphael. His fiancée, Maria Bibbiena is buried to the right of his sarcophagus; she died before they could marry. The sarcophagus was given by Pope Gregory XVI, and its inscription reads ILLE HIC EST RAPHAEL TIMUIT QUO SOSPITE VINCI / RERUM MAGNA PARENS ET MORIENTE MORI, meaning "Here lies Raphael, by whom the great mother of all things (Nature) feared to be overcome while he was living, and while he was dying, herself to die". The epigraph was written by Pietro Bembo.

The present arrangement is from 1811, designed by Antonio Muñoz. The bust of Raphael (1833) is by Giuseppe Fabris. The two plaques commemorate Maria Bibbiena and Annibale Carracci. Behind the tomb is the statue known as the Madonna del Sasso (Madonna of the Rock) so named because she rests one foot on a boulder. It was commissioned by Raphael and made by Lorenzetto in 1524.

In the Chapel of the Crucifixion, the Roman brick wall is visible in the niches. The wooden crucifix on the altar is from the 15th century. On the left wall is a Descent of the Holy Ghost (1790) by Pietro Labruzi. On the right side is the low relief Cardinal Consalvi presents to Pope Pius VII the five provinces restored to the Holy See (1824) made by the Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen. The bust is a portrait of Cardinal Agostino Rivarola. The final niche on this side has a statue of St. Evasius (Sant'Evasio) (1727) by Francesco Moderati.[68]

Gallery

-

The dome photographed with a fisheye lens in 2016

-

South east view of the Pantheon from Piazza della Minerva, 2006

-

Tomb of King Victor Emmanuel II, "Father of his Country"

Influence

As the best-preserved example of an Ancient Roman monumental building, the Pantheon has been enormously influential in Western architecture from at least the Renaissance on;[69] starting with Brunelleschi's 42-metre (138 ft) dome of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, completed in 1436.[70]

Among the most notable versions are the church of Santa Maria Assunta (1664) in Ariccia by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, which followed his work restoring the Roman original,[71] Belle Isle House (1774) in England and Thomas Jefferson's library at the University of Virginia, The Rotunda (1817–1826).[71] Others include the Rotunda of Mosta in Malta (1833).[72] Other notable replicas, such as The Rotunda (New York) (1818), do not survive.[73]

The portico-and-dome form of the Pantheon can be detected in many buildings of the 19th and 20th centuries; numerous government and public buildings, city halls, university buildings, and public libraries echo its structure.[74]

See also

- Romanian Athenaeum

- Panthéon, Paris

- Pantheon, Moscow (never built)

- Manchester Central Library

- Volkshalle higher (never built)

- The Rotunda (University of Virginia) US

- Auditorium of Southeast University, Southeast University, China

General:

- List of Ancient Roman temples

- List of the oldest buildings in the world

- List of Roman domes

- History of Roman and Byzantine domes

- List of largest domes

- List of tallest domes

- Roman engineering

- Roman technology

Notes

- ^ Although the spelling Pantheon is standard in English, only Pantheum is found in classical Latin; see, for example, Pliny, Natural History 36.38: "Agrippas Pantheum decoravit Diogenes Atheniensis". See also Oxford Latin Dictionary, s.v. "Pantheum"; Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. "Pantheon": "post-classical Latin pantheon a temple consecrated to all the gods (6th cent.; compare classical Latin pantheum)".

Footnotes

- ^ Jump up to:a b "Pantheon". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. December 2008.

- ^ MacDonald 1976, pp. 12–13

- ^ Jump up to:a b Moore, David (1999). "The Pantheon". romanconcrete.com. Retrieved September 26, 2011.

- ^ Rasch 1985, p. 119

- ^ Jump up to:a b MacDonald 1976, p. 18

- ^ Summerson (1980), 38–39, 38 quoted

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman Histories 53.27, referenced in MacDonald 1976, p. 76

- ^ Ziolkowski, Adam (1994). "Was Agrippa's Pantheon the Temple of Mars 'In Campo'?". Papers of the British School at Rome. 62: 271. doi:10.1017/S0068246200010084.

- ^ Thomas, Edmund (2004). "From the Pantheon of the Gods to the Pantheon of Rome". In Richard Wrigley; Matthew Craske (eds.). Pantheons; Transformations of a Monumental Idea. Aldershot: Ashgate. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-7546-0808-0.

- ^ Ziegler, Konrat (1949). "Pantheion". Pauly's Real-Encyclopädie der Classischen Altertumswissenschaft: neue Bearbeitung. Vol. XVIII. Stuttgart. pp. 697–747.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Godfrey, Paul; Hemsoll, David (1986). "The Pantheon: Temple or Rotunda?". In Martin Henig; Anthony King (eds.). Pagan Gods and Shrines of the Roman Empire (Monograph No 8 ed.). Oxford University Committee for Archaeology. p. 199.

- ^ Ziolkowski, Adam (1994). "Was Agrippa's Pantheon the Temple of Mars 'In Campo'?". Papers of the British School at Rome. 62: 265. doi:10.1017/S0068246200010084.

- ^ Godfrey, Paul; Hemsoll, David (1986). "The Pantheon: Temple or Rotunda?". In Martin Henig; Anthony King (eds.). Pagan Gods and Shrines of the Roman Empire (Monograph No 8 ed.). Oxford University Committee for Archaeology. p. 198.

- ^ Dio, Cassius. "Roman History". p. 53.23.3.

- ^ Ziolkowski, Adam (1999). Lexicon topographicum urbis Romae 4. Rome: Quasar. pp. 55–56.

- ^ Ziolkowski, Adam (1994). "Was Agrippa's Pantheon the Temple of Mars 'In Campo'?". Papers of the British School at Rome. 62: 261–277. doi:10.1017/S0068246200010084.

- ^ Ziolkowski, Adam (1994). "Was Agrippa's Pantheon the Temple of Mars 'In Campo'?". Papers of the British School at Rome. 62: 275. doi:10.1017/S0068246200010084.

- ^ Thomas 1997, p. 165

- ^ "Pantheon". Romereborn.virginia.edu. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ^ Hetland, Lise (November 9–12, 2006). Graßhoff, G; Heinzelmann, M; Wäfler, M (eds.). "Zur Datierung des Pantheon". The Pantheon in Rome: Contributions Contributions to the Conference. Bern.

- ^ Ziolkowski, Adam (November 9–12, 2006). Graßhoff, G; Heinzelmann, M; Wäfler, M (eds.). "What did Agrippa's Pantheon Look like? New Answers to an Old Question". The Pantheon in Rome: Contributions to the Conference. Bern: 31–34.

- ^ Pliny, The Elder. "The Natural History". p. 34.7.

- ^ Pliny, The Elder. "The Natural History". p. 36.4.

- ^ Pliny, The Elder. "The Natural History". p. 9.58.

- ^ Kleiner 2007, p. 182

- ^ Ramage & Ramage 2009, p. 236

- ^ Ziolkowski, Adam (November 9–12, 2006). Graßhoff, G; Heinzelmann, M; Wäfler, M (eds.). "What did Agrippa's Pantheon Look like? New Answers to an Old Question". The Pantheon in Rome: Contributions to the Conference. Bern: 39.

- ^ Ziolkowski, Adam (2007). Leone; Palombi; Walker (eds.). Res Bene Gestae: Ricerche di storia urbana su Roma antica in onore di Eva Margreta Steinby. Rome: Quasar.

- ^ Luigi Piale; Mariano Vasi (1851). New Guide of Rome and the Environs According to Vasi and Nibby: Containing a Description of the Monuments, Galleries, Churches [etc.] Carefully Revised and Enlarged, with an Account of the Latest Antiquarian Researches. L. Piale. p. 272.

- ^ Giuseppe Melchiorri (1834). Paolo Badalì (ed.). "Nuova guida metodica di Roma e suoi contorni – Parte Terza ("New Methodic Guide to Rome and Its Suburbs – Third Part")". Archivio viaggiatori italiani a roma e nel lazio – Istituto Nazionale Di Studi Romani (in Italian). Tuscia University. Archived from the original on 3 March 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ Emmanuel Rodocanachi (1920). Les monuments antiques de Rome encore existants: les ponts, les murs, les voies, les aqueducs, les enceintes de Rome, les palais, les temples, les arcs (in French). Libr. Hachette. p. 192.

- ^ John the Deacon, Monumenta Germaniae Historia (1848) 7.8.20, quoted in MacDonald 1976, p. 139

- ^ Popes Boniface III-VII (archived copy) oce.catholic.com, accessed 11 April 2021

- ^ Andrew J. Ekonomou. Byzantine Rome and the Greek Popes. Lexington books, Toronto, 2007

- ^ British Museum Highlights Archived 2015-10-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mormando, Franco (2011). Bernini: His Life and His Rome. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-53851-8. Retrieved January 3, 2012.

- ^ DuTemple, Leslie A. (2003). The Pantheon. Minneapolis: Lerner Publns. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-8225-0376-7. Retrieved May 8, 2011.

bernini pantheon towers.

- ^ Marder 1991, p. 275

- ^ Another view of the interior by Panini (1735), Liechtenstein Museum, Vienna Archived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Pantheon, The ruins and excavations of ancient Rome". Rodolpho Lanciani. Archived from the original on 2007-07-01.

- ^ MacDonald 1976, pp. 63, 141–142; Claridge 1998, p. 203

- ^ Jump up to:a b Wilson-Jones 2003, The Enigma of the Pantheon: The Exterior, pp. 199–206

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Taylor, Rabun (2003). Roman Builders, a study in architectural process. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 129–131. ISBN 0521803349.

- ^ MacDonald, William L. (1965). The Architecture of the Roman Empire, vol. 1: An Introductory Study. Yale University Press. pp. 111–113. ISBN 9780300028195.

- ^ Parker, Freda. "The Pantheon – Rome – 126 AD". Monolithic. Archived from the original on 2009-05-26. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

- ^ Wilson-Jones 2003, The Enigma of the Pantheon: The Exterior, pp. 206–212

- ^ Wilson-Jones 2003, The Enigma of the Pantheon: The Exterior, pp. 206–207

- ^ Jump up to:a b Cinti et al. 2007, p. 29

- ^ Claridge 1998, p. 204

- ^ Jump up to:a b Cowan 1977, p. 56

- ^ Wilson-Jones 2003, p. 187, Principles of Roman Architecture

- ^ Mark & Hutchinson 1986

- ^ MacDonald 1976, p. 33 "There are openings in it [the rotunda] here and there, at various levels, that give on to some of the many different chambers that honeycomb the rotunda structure, a honeycombing that is an integral part of a sophisticated engineering solution..."

- ^ Moore, David (February 1993). "The Riddle of Ancient Roman Concrete". S Dept. of the Interior, Bureau of Reclamation, Upper Colorado Region. www.romanconcrete.com. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Roth 1992, p. 36

- ^ Claridge 1998, pp. 204–205

- ^ Lancaster 2005, pp. 44–46

- ^ Ottoni, Federica; Blasi, Carlo (March 4, 2015). "Hooping as an Ancient Remedy for Conservation of Large Masonry Domes". International Journal of Architectural Heritage.

- ^ MacDonald 1976, p. 34, Wilson-Jones 2003, p. 191

- ^ "Roman Pantheon". www.rome.info. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- ^ "Pantheon". history.com. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- ^ Wilson-Jones 2003, The Enigma of the Pantheon: The Interior, pp. 182–184

- ^ Lancaster 2005, p. 46

- ^ Wilson-Jones 2003, The Enigma of the Pantheon: The Interior, pp. 182–183.

- ^ De la Croix, Horst; Tansey, Richard G.; Kirkpatrick, Diane (1991). Gardner's Art Through the Ages (9th ed.). Thomson/Wadsworth. p. 228. ISBN 0-15-503769-2.

- ^ Wilson-Jones 2003, The Enigma of the Pantheon: The Interior, pp. 184–197

- ^ Jump up to:a b Marder 1980, p. 35

- ^ MacDonald 1976, pp. 94–132

- ^ King 2000

- ^ Jump up to:a b Summerson (1980), 38–39

- ^ Schiavone, Michael J. (2009). Dictionary of Maltese Biographies Vol. 2 G–Z. Pietà: Pubblikazzjonijiet Indipendenza. pp. 989–990. ISBN 9789993291329.

- ^ Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. Oxford University Press. 1998. p. 468.

- ^ MacDonald, William Lloyd (2002). The Pantheon: Design, Meaning, and Progeny. Harvard University Press. p. 94. ISBN 9780674010192.

References

- Cinti, Siro; De Martino, Federico; Carandini, Andrea; De Carolis, Marco; Belardi, Giovanni (2007). Pantheon. Storia e Futuro / History and Future (in Italian). Rome, Italy: Gangemi Editore. ISBN 978-88-492-1301-0.

- Claridge, Amanda (1998). Rome. Oxford Archaeological Guides. Oxford Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-288003-9.

- Cowan, Henry (1977). The Master Builders: : A History of Structural and Environmental Design From Ancient Egypt to the Nineteenth Century. New York: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0-471-02740-5.

- Favro, Diane (2005). "Making Rome a World City". The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Augustus. Cambridge University Press. pp. 234–263. ISBN 978-0-521-00393-3.

- Hetland, L. M. (2007). "Dating the Pantheon". Journal of Roman Archaeology. 20 (1): 95–112. doi:10.1017/S1047759400005328. ISSN 1047-7594.

- King, Ross (2000). Brunelleschi's Dome. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 0-7011-6903-6.

- Kleiner, Fred S. (2007). A History of Roman Art. Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing. ISBN 978-0-534-63846-7.

- Lancaster, Lynne C. (2005). Concrete Vaulted Construction in Imperial Rome: Innovations in Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-84202-6.

- Loewenstein, Karl (1973). The Governance of Rome. The Hague, Netherlands: Martinus Nijhof. ISBN 978-90-247-1458-2.

- MacDonald, William L. (1976). The Pantheon: Design, Meaning, and Progeny. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01019-1.

- Marder, Tod A. (1980). "Specchi's High Altar for the Pantheon and the Statues by Cametti and Moderati". The Burlington Magazine. The Burlington Magazine Publications, Ltd. 122 (922): 30–40. JSTOR 879867.

- Marder, Tod A. (1991). "Alexander VII, Bernini, and the Urban Setting of the Pantheon in the Seventeenth Century". The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. Society of Architectural Historians. 50 (3): 273–292. doi:10.2307/990615. JSTOR 990615.

- Mark, R.; Hutchinson, P. (1986). "On the structure of the Pantheon". Art Bulletin. College Art Association. 68 (1): 24–34. doi:10.2307/3050861. JSTOR 3050861.

- Ramage, Nancy H.; Ramage, Andrew (2009). Roman art : Romulus to Constantine (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-600097-6.

- Rasch, Jürgen (1985). "Die Kuppel in der römischen Architektur. Entwicklung, Formgebung, Konstruktion, Architectura". Architectura. 15: 117–139.

- Roth, Leland M. (1992). Understanding Architecture: Its Elements, History, And Meaning. Boulder: Westview Press. ISBN 0-06-438493-4.

- Stamper, John W. (2005). The Architecture Of Roman Temples: The Republic To The Middle Empire. The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-81068-X.

- Summerson, John (1980), The Classical Language of Architecture, 1980 edition, Thames and Hudson World of Art series, ISBN 0-500-20177-3

- Thomas, Edmund (1997). "The Architectural History of the Pantheon from Agrippa to Septimius Severus via Hadrian". Hephaistos. 15: 163–186.

- Wilson-Jones, Mark (2003). Principles of Roman Architecture. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10202-X.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pantheon (Roma). |

| Library resources about Pantheon |

- Official webpage from Vicariate of Rome website

- Pantheon Live Webcam, Live streaming Video of the Pantheon

- Pantheon Rome, Virtual Panorama and photo gallery

- Pantheon, article in Platner's Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome

- Pantheon Rome vs Pantheon Paris

- Tomás García Salgado, "The geometry of the Pantheon's vault"

- Pantheon at Great Buildings/Architecture Week website

- Art & History Pantheon Archived 2010-11-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Summer solstice at the Pantheon

- Pantheon at Structurae

- Video Introduction to the Pantheon

- Panoramic Virtual Tour inside the Pantheon

- High-resolution 360° Panoramas and Images of Pantheon | Art Atlas

- audio guide Pantheon Rome

- 128

- 2nd-century religious buildings and structures

- 7th-century churches in Italy

- Basilica churches in Rome

- Temples in the Campus Martius

- Ancient Roman buildings and structures in Rome

- Concrete shell structures

- Augustan building projects

- Hadrianic building projects

- Church buildings with domes

- Round churches

- Conversion of non-Christian religious buildings and structures into churches

- Tourist attractions in Rome

- Rome R. IX Pigna

- Centralized-plan churches in Italy

- Hadrian

- Roman temples by deity

- Buildings converted to Catholic church buildings

- Burial sites of the House of Savoy

- Details

- Written by Super User

- Category: Rome

- Hits: 4628

Rome

|

Rome

Roma (Italian)

|

|

|---|---|

|

Capital city and comune

|

|

| Roma Capitale | |

Clockwise from top: the Colosseum, St. Peter's Basilica, Castel Sant'Angelo, Ponte Sant'Angelo, Trevi Fountain and the Pantheon

|

|

| Etymology: Possibly Etruscan: Rumon, lit. 'river' | |

| Nickname(s): | |

The territory of the comune (Roma Capitale, in red) inside the Metropolitan City of Rome (Città Metropolitana di Roma, in yellow). The white spot in the centre is Vatican City.

|

|

| Coordinates: 41°53′36″N 12°28′58″ECoordinates: 41°53′36″N 12°28′58″E | |

| Country | |

| Region | |

| Metropolitan city | |

| Founded | 753 BC |

| Founded by | King Romulus |

| Government

|

|

| • Type | Strong Mayor–Council |

| • Mayor | Roberto Gualtieri (PD) |

| • Legislature | Capitoline Assembly |

| Area

|

|

| • Total | 1,285 km2 (496.3 sq mi) |

| Elevation

|

21 m (69 ft) |

| Population

(31 December 2019)

|

|

| • Rank | 1st in Italy (3rd in the EU) |

| • Density | 2,236/km2 (5,790/sq mi) |

| • Comune

|

2,860,009[1] |

| • Metropolitan City

|

4,342,212[2] |

| Demonym(s) | Italian: romano(i) (masculine), romana(e) (feminine) English: Roman(s) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| CAP code(s) |

00100; 00118 to 00199

|

| Area code(s) | 06 |

| Website | comune.roma.it |

| Official name | Historic Centre of Rome, the Properties of the Holy See in that City Enjoying Extraterritorial Rights and San Paolo Fuori le Mura |

| Reference | 91 |

| Inscription | 1980 (4th Session) |

| Area | 1,431 ha (3,540 acres) |

Rome (Italian and Latin: Roma [ˈroːma] (![]() listen)) is the capital city of Italy. It is also the capital of the Lazio region, the centre of the Metropolitan City of Rome, and a special comune named Comune di Roma Capitale. With 2,860,009 residents in 1,285 km2 (496.1 sq mi),[1] Rome is the country's most populated comune and the third most populous city in the European Union by population within city limits. The Metropolitan City of Rome, with a population of 4,355,725 residents, is the most populous metropolitan city in Italy.[2] Its metropolitan area is the third-most populous within Italy.[3] Rome is located in the central-western portion of the Italian Peninsula, within Lazio (Latium), along the shores of the Tiber. Vatican City (the smallest country in the world)[4] is an independent country inside the city boundaries of Rome, the only existing example of a country within a city. Rome is often referred to as the City of Seven Hills due to its geographic location, and also as the "Eternal City".[5] Rome is generally considered to be the "cradle of Western Christian culture and civilization", and the center of the Catholic Church.[6][7][8]

listen)) is the capital city of Italy. It is also the capital of the Lazio region, the centre of the Metropolitan City of Rome, and a special comune named Comune di Roma Capitale. With 2,860,009 residents in 1,285 km2 (496.1 sq mi),[1] Rome is the country's most populated comune and the third most populous city in the European Union by population within city limits. The Metropolitan City of Rome, with a population of 4,355,725 residents, is the most populous metropolitan city in Italy.[2] Its metropolitan area is the third-most populous within Italy.[3] Rome is located in the central-western portion of the Italian Peninsula, within Lazio (Latium), along the shores of the Tiber. Vatican City (the smallest country in the world)[4] is an independent country inside the city boundaries of Rome, the only existing example of a country within a city. Rome is often referred to as the City of Seven Hills due to its geographic location, and also as the "Eternal City".[5] Rome is generally considered to be the "cradle of Western Christian culture and civilization", and the center of the Catholic Church.[6][7][8]

Rome's history spans 28 centuries. While Roman mythology dates the founding of Rome at around 753 BC, the site has been inhabited for much longer, making it a major human settlement for almost three millennia and one of the oldest continuously occupied cities in Europe.[9] The city's early population originated from a mix of Latins, Etruscans, and Sabines. Eventually, the city successively became the capital of the Roman Kingdom, the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire, and is regarded by many as the first-ever Imperial city and metropolis.[10] It was first called The Eternal City (Latin: Urbs Aeterna; Italian: La Città Eterna) by the Roman poet Tibullus in the 1st century BC, and the expression was also taken up by Ovid, Virgil, and Livy.[11][12] Rome is also called "Caput Mundi" (Capital of the World). After the fall of the Empire in the west, which marked the beginning of the Middle Ages, Rome slowly fell under the political control of the Papacy, and in the 8th century, it became the capital of the Papal States, which lasted until 1870. Beginning with the Renaissance, almost all popes since Nicholas V (1447–1455) pursued a coherent architectural and urban programme over four hundred years, aimed at making the city the artistic and cultural centre of the world.[13] In this way, Rome became first one of the major centres of the Renaissance,[14] and then the birthplace of both the Baroque style and Neoclassicism. Famous artists, painters, sculptors, and architects made Rome the centre of their activity, creating masterpieces throughout the city. In 1871, Rome became the capital of the Kingdom of Italy, which, in 1946, became the Italian Republic.

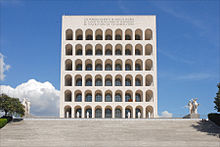

In 2019, Rome was the 11th most visited city in the world, with 10.1 million tourists, the third most visited in the European Union, and the most popular tourist destination in Italy.[15] Its historic centre is listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site.[16] The host city for the 1960 Summer Olympics, Rome is also the seat of several specialised agencies of the United Nations, such as the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the World Food Programme (WFP) and the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). The city also hosts the Secretariat of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Union for the Mediterranean[17] (UfM) as well as the headquarters of many international businesses, such as Eni, Enel, TIM, Leonardo S.p.A., and national and international banks such as Unicredit and BNL. Rome's EUR business district is the home of many oil industry, the pharmaceutical industry, and financial services companies. The presence of renowned international brands in the city has made Rome an important centre of fashion and design, and the Cinecittà Studios have been the set of many Academy Award–winning movies.[18]

Contents

Etymology

According to the Ancient Romans' founding myth,[19] the name Roma came from the city's founder and first king, Romulus.[20]

However, it is possible that the name Romulus was actually derived from Rome itself.[21] As early as the 4th century, there have been alternative theories proposed on the origin of the name Roma. Several hypotheses have been advanced focusing on its linguistic roots which however remain uncertain:[22]

- From Rumon or Rumen, archaic name of the Tiber, which in turn is supposedly related to the Greek verb ῥέω (rhéō) 'to flow, stream' and the Latin verb ruō 'to hurry, rush';[b]

- From the Etruscan word 𐌓𐌖𐌌𐌀 (ruma), whose root is *rum- "teat", with possible reference either to the totem wolf that adopted and suckled the cognately named twins Romulus and Remus, or to the shape of the Palatine and Aventine Hills;

- From the Greek word ῥώμη (rhṓmē), which means strength.[c]

History

Latins (Italic tribe) c. 2nd millennium – 752 BC

Albanis (Latins) 10th century – 752 BC

(Foundation of the city) 9th–c. BCRoman Kingdom 752–509 BC

Roman Republic 509–27 BC

Roman Empire 27 BC–395 AD

Western Roman Empire 395–476

Kingdom of Odoacer 476–493

Ostrogothic Kingdom 493–553

Eastern Roman Empire 553–754

Papal States 754–1798, 1799–1809, 1814–1849, 1849–1870

Roman Republic 1798–1799

First French Empire 1809–1814

Roman Republic 1849

Kingdom of Italy 1870–1946

Vatican City 1929–present

Italian Republic 1946–present

Earliest history

While there have been discoveries of archaeological evidence of human occupation of the Rome area from approximately 14,000 years ago, the dense layer of much younger debris obscures Palaeolithic and Neolithic sites.[9] Evidence of stone tools, pottery, and stone weapons attest to about 10,000 years of human presence. Several excavations support the view that Rome grew from pastoral settlements on the Palatine Hill built above the area of the future Roman Forum. Between the end of the Bronze Age and the beginning of the Iron Age, each hill between the sea and the Capitol was topped by a village (on the Capitol Hill, a village is attested since the end of the 14th century BC).[23] However, none of them yet had an urban quality.[23] Nowadays, there is a wide consensus that the city developed gradually through the aggregation ("synoecism") of several villages around the largest one, placed above the Palatine.[23] This aggregation was facilitated by the increase of agricultural productivity above the subsistence level, which also allowed the establishment of secondary and tertiary activities. These, in turn, boosted the development of trade with the Greek colonies of southern Italy (mainly Ischia and Cumae).[23] These developments, which according to archaeological evidence took place during the mid-eighth century BC, can be considered as the "birth" of the city.[23] Despite recent excavations at the Palatine hill, the view that Rome was founded deliberately in the middle of the eighth century BC, as the legend of Romulus suggests, remains a fringe hypothesis.[24]

Legend of the founding of Rome

Traditional stories handed down by the ancient Romans themselves explain the earliest history of their city in terms of legend and myth. The most familiar of these myths, and perhaps the most famous of all Roman myths, is the story of Romulus and Remus, the twins who were suckled by a she-wolf.[19] They decided to build a city, but after an argument, Romulus killed his brother and the city took his name. According to the Roman annalists, this happened on 21 April 753 BC.[25] This legend had to be reconciled with a dual tradition, set earlier in time, that had the Trojan refugee Aeneas escape to Italy and found the line of Romans through his son Iulus, the namesake of the Julio-Claudian dynasty.[26] This was accomplished by the Roman poet Virgil in the first century BC. In addition, Strabo mentions an older story, that the city was an Arcadian colony founded by Evander. Strabo also writes that Lucius Coelius Antipater believed that Rome was founded by Greeks.[27][28]

Monarchy and republic

After the foundation by Romulus according to a legend,[25] Rome was ruled for a period of 244 years by a monarchical system, initially with sovereigns of Latin and Sabine origin, later by Etruscan kings. The tradition handed down seven kings: Romulus, Numa Pompilius, Tullus Hostilius, Ancus Marcius, Tarquinius Priscus, Servius Tullius and Lucius Tarquinius Superbus.[25]

In 509 BC, the Romans expelled the last king from their city and established an oligarchic republic. Rome then began a period characterised by internal struggles between patricians (aristocrats) and plebeians (small landowners), and by constant warfare against the populations of central Italy: Etruscans, Latins, Volsci, Aequi, and Marsi.[29] After becoming master of Latium, Rome led several wars (against the Gauls, Osci-Samnites and the Greek colony of Taranto, allied with Pyrrhus, king of Epirus) whose result was the conquest of the Italian peninsula, from the central area up to Magna Graecia.[30]

The third and second century BC saw the establishment of Roman hegemony over the Mediterranean and the Balkans, through the three Punic Wars (264–146 BC) fought against the city of Carthage and the three Macedonian Wars (212–168 BC) against Macedonia.[31] The first Roman provinces were established at this time: Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica, Hispania, Macedonia, Achaea and Africa.[32]

From the beginning of the 2nd century BC, power was contested between two groups of aristocrats: the optimates, representing the conservative part of the Senate, and the populares, which relied on the help of the plebs (urban lower class) to gain power. In the same period, the bankruptcy of the small farmers and the establishment of large slave estates caused large-scale migration to the city. The continuous warfare led to the establishment of a professional army, which turned out to be more loyal to its generals than to the republic. Because of this, in the second half of the second century and during the first century BC there were conflicts both abroad and internally: after the failed attempt of social reform of the populares Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus,[33] and the war against Jugurtha,[33] there was a civil war from which the general Sulla emerged victorious.[33] A major slave revolt under Spartacus followed,[34][34] and then the establishment of the first Triumvirate with Caesar, Pompey and Crassus.[34]

The conquest of Gaul made Caesar immensely powerful and popular, which led to a second civil war against the Senate and Pompey. After his victory, Caesar established himself as dictator for life.[34] His assassination led to a second Triumvirate among Octavian (Caesar's grandnephew and heir), Mark Antony and Lepidus, and to another civil war between Octavian and Antony.[35]

Empire

In 27 BC, Octavian became princeps civitatis and took the title of Augustus, founding the principate, a diarchy between the princeps and the senate.[35] During the reign of Nero, two thirds of the city was ruined after the Great Fire of Rome, and the persecution of Christians commenced.[36][37][38] Rome was established as a de facto empire, which reached its greatest expansion in the second century under the Emperor Trajan. Rome was confirmed as caput Mundi, i.e. the capital of the known world, an expression which had already been used in the Republican period. During its first two centuries, the empire was ruled by emperors of the Julio-Claudian,[39] Flavian (who also built an eponymous amphitheatre, known as the Colosseum),[39] and Antonine dynasties.[40] This time was also characterised by the spread of the Christian religion, preached by Jesus Christ in Judea in the first half of the first century (under Tiberius) and popularised by his apostles through the empire and beyond.[41] The Antonine age is considered the zenith of the Empire, whose territory ranged from the Atlantic Ocean to the Euphrates and from Britain to Egypt.[40]

After the end of the Severan Dynasty in 235, the Empire entered into a 50-year period known as the Crisis of the Third Century during which there were numerous putsches by generals, who sought to secure the region of the empire they were entrusted with due to the weakness of central authority in Rome. There was the so-called Gallic Empire from 260 to 274 and the revolts of Zenobia and her father from the mid-260s which sought to fend off Persian incursions. Some regions – Britain, Spain, and North Africa – were hardly affected. Instability caused economic deterioration, and there was a rapid rise in inflation as the government debased the currency in order to meet expenses. The Germanic tribes along the Rhine and north of the Balkans made serious, uncoordinated incursions from the 250s-280s that were more like giant raiding parties rather than attempts to settle. The Persian Empire invaded from the east several times during the 230s to 260s but were eventually defeated.[44] Emperor Diocletian (284) undertook the restoration of the State. He ended the Principate and introduced the Tetrarchy which sought to increase state power. The most marked feature was the unprecedented intervention of the State down to the city level: whereas the State had submitted a tax demand to a city and allowed it to allocate the charges, from his reign the State did this down to the village level. In a vain attempt to control inflation, he imposed price controls which did not last. He or Constantine regionalised the administration of the empire which fundamentally changed the way it was governed by creating regional dioceses (the consensus seems to have shifted from 297 to 313/14 as the date of creation due to the argument of Constantin Zuckerman in 2002 "Sur la liste de Verone et la province de grande armenie, Melanges Gilber Dagron). The existence of regional fiscal units from 286 served as the model for this unprecedented innovation. The emperor quickened the process of removing military command from governors. Henceforth, civilian administration and military command would be separate. He gave governors more fiscal duties and placed them in charge of the army logistical support system as an attempt to control it by removing the support system from its control. Diocletian ruled the eastern half, residing in Nicomedia. In 296, he elevated Maximian to Augustus of the western half, where he ruled mostly from Mediolanum when not on the move.[44] In 292, he created two 'junior' emperors, the Caesars, one for each Augustus, Constantius for Britain, Gaul, and Spain whose seat of power was in Trier and Galerius in Sirmium in the Balkans. The appointment of a Caesar was not unknown: Diocletian tried to turn into a system of non-dynastic succession. Upon abdication in 305, the Caesars succeeded and they, in turn, appointed two colleagues for themselves.[44]

After the abdication of Diocletian and Maximian in 305 and a series of civil wars between rival claimants to imperial power, during the years 306–313, the Tetrarchy was abandoned. Constantine the Great undertook a major reform of the bureaucracy, not by changing the structure but by rationalising the competencies of the several ministries during the years 325–330, after he defeated Licinius, emperor in the East, at the end of 324. The so-called Edict of Milan of 313, actually a fragment of a letter from Licinius to the governors of the eastern provinces, granted freedom of worship to everyone, including Christians, and ordered the restoration of confiscated church properties upon petition to the newly created vicars of dioceses. He funded the building of several churches and allowed clergy to act as arbitrators in civil suits (a measure that did not outlast him but which was restored in part much later). He transformed the town of Byzantium into his new residence, which, however, was not officially anything more than an imperial residence like Milan or Trier or Nicomedia until given a city prefect in May 359 by Constantius II; Constantinople.[45]

Christianity in the form of the Nicene Creed became the official religion of the empire in 380, via the Edict of Thessalonica issued in the name of three emperors – Gratian, Valentinian II, and Theodosius I – with Theodosius clearly the driving force behind it. He was the last emperor of a unified empire: after his death in 395, his sons, Arcadius and Honorius divided the empire into a western and an eastern part. The seat of government in the Western Roman Empire was transferred to Ravenna after the Siege of Milan in 402. During the 5th century, the emperors from the 430s mostly resided in the capital city, Rome.[45]

Rome, which had lost its central role in the administration of the empire, was sacked in 410 by the Visigoths led by Alaric I,[46] but very little physical damage was done, most of which were repaired. What could not be so easily replaced were portable items such as artwork in precious metals and items for domestic use (loot). The popes embellished the city with large basilicas, such as Santa Maria Maggiore (with the collaboration of the emperors). The population of the city had fallen from 800,000 to 450–500,000 by the time the city was sacked in 455 by Genseric, king of the Vandals.[47] The weak emperors of the fifth century could not stop the decay, leading to the deposition of Romulus Augustus on 22 August 476, which marked the end of the Western Roman Empire and, for many historians, the beginning of the Middle Ages.[45] The decline of the city's population was caused by the loss of grain shipments from North Africa, from 440 onward, and the unwillingness of the senatorial class to maintain donations to support a population that was too large for the resources available. Even so, strenuous efforts were made to maintain the monumental centre, the palatine, and the largest baths, which continued to function until the Gothic siege of 537. The large baths of Constantine on the Quirinale were even repaired in 443, and the extent of the damage exaggerated and dramatised.[48] However, the city gave an appearance overall of shabbiness and decay because of the large abandoned areas due to population decline. The population declined to 500,000 by 452 and 100,000 by 500 AD (perhaps larger, though no certain figure can be known). After the Gothic siege of 537, the population dropped to 30,000 but had risen to 90,000 by the papacy of Gregory the Great.[49] The population decline coincided with the general collapse of urban life in the West in the fifth and sixth centuries, with few exceptions. Subsidized state grain distributions to the poorer members of society continued right through the sixth century and probably prevented the population from falling further.[50] The figure of 450,000–500,000 is based on the amount of pork, 3,629,000 lbs. distributed to poorer Romans during five winter months at the rate of five Roman lbs per person per month, enough for 145,000 persons or 1/4 or 1/3 of the total population.[51] Grain distribution to 80,000 ticket holders at the same time suggests 400,000 (Augustus set the number at 200,000 or one-fifth of the population).

Middle Ages

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD, Rome was first under the control of Odoacer and then became part of the Ostrogothic Kingdom before returning to East Roman control after the Gothic War, which devastated the city in 546 and 550. Its population declined from more than a million in 210 AD to 500,000 in 273[52] to 35,000 after the Gothic War (535–554),[53] reducing the sprawling city to groups of inhabited buildings interspersed among large areas of ruins, vegetation, vineyards and market gardens.[54] It is generally thought the population of the city until 300 AD was 1 million (estimates range from 2 million to 750,000) declining to 750–800,000 in 400 AD, 450–500,000 in 450 AD and down to 80–100,000 in 500 AD (though it may have been twice this).[55]

The Bishop of Rome, called the Pope, was important since the early days of Christianity because of the martyrdom of both the apostles Peter and Paul there. The Bishops of Rome were also seen (and still are seen by Catholics) as the successors of Peter, who is considered the first Bishop of Rome. The city thus became of increasing importance as the centre of the Catholic Church.

After the Lombard invasion of Italy (569–572), the city remained nominally Byzantine, but in reality, the popes pursued a policy of equilibrium between the Byzantines, the Franks, and the Lombards.[56] In 729, the Lombard king Liutprand donated the north Latium town of Sutri to the Church, starting its temporal power.[56] In 756, Pepin the Short, after having defeated the Lombards, gave the Pope temporal jurisdiction over the Roman Duchy and the Exarchate of Ravenna, thus creating the Papal States.[56] Since this period, three powers tried to rule the city: the pope, the nobility (together with the chiefs of militias, the judges, the Senate and the populace), and the Frankish king, as king of the Lombards, patricius, and Emperor.[56] These three parties (theocratic, republican, and imperial) were a characteristic of Roman life during the entire Middle Ages.[56] On Christmas night of 800, Charlemagne was crowned in Rome as emperor of the Holy Roman Empire by Pope Leo III: on that occasion, the city hosted for the first time the two powers whose struggle for control was to be a constant of the Middle Ages.[56]

In 846, Muslim Arabs unsuccessfully stormed the city's walls, but managed to loot St. Peter's and St. Paul's basilica, both outside the city wall.[57] After the decay of Carolingian power, Rome fell prey to feudal chaos: several noble families fought against the pope, the emperor, and each other. These were the times of Theodora and her daughter Marozia, concubines and mothers of several popes, and of Crescentius, a powerful feudal lord, who fought against the Emperors Otto II and Otto III.[58] The scandals of this period forced the papacy to reform itself: the election of the pope was reserved to the cardinals, and reform of the clergy was attempted. The driving force behind this renewal was the monk Ildebrando da Soana, who once elected pope under the name of Gregory VII became involved into the Investiture Controversy against Emperor Henry IV.[58] Subsequently, Rome was sacked and burned by the Normans under Robert Guiscard who had entered the city in support of the Pope, then besieged in Castel Sant'Angelo.[58]

During this period, the city was autonomously ruled by a senatore or patrizio. In the 12th century, this administration, like other European cities, evolved into the commune, a new form of social organisation controlled by the new wealthy classes.[58] Pope Lucius II fought against the Roman commune, and the struggle was continued by his successor Pope Eugenius III: by this stage, the commune, allied with the aristocracy, was supported by Arnaldo da Brescia, a monk who was a religious and social reformer.[59] After the pope's death, Arnaldo was taken prisoner by Adrianus IV, which marked the end of the commune's autonomy.[59] Under Pope Innocent III, whose reign marked the apogee of the papacy, the commune liquidated the senate, and replaced it with a Senatore, who was subject to the pope.[59]

In this period, the papacy played a role of secular importance in Western Europe, often acting as arbitrators between Christian monarchs and exercising additional political powers.[60][61][62]

In 1266, Charles of Anjou, who was heading south to fight the Hohenstaufen on behalf of the pope, was appointed Senator. Charles founded the Sapienza, the university of Rome.[59] In that period the pope died, and the cardinals, summoned in Viterbo, could not agree on his successor. This angered the people of the city, who then unroofed the building where they met and imprisoned them until they had nominated the new pope; this marked the birth of the conclave.[59] In this period the city was also shattered by continuous fights between the aristocratic families: Annibaldi, Caetani, Colonna, Orsini, Conti, nested in their fortresses built above ancient Roman edifices, fought each other to control the papacy.[59]

Pope Boniface VIII, born Caetani, was the last pope to fight for the church's universal domain; he proclaimed a crusade against the Colonna family and, in 1300, called for the first Jubilee of Christianity, which brought millions of pilgrims to Rome.[59] However, his hopes were crushed by the French king Philip the Fair, who took him prisoner and killed him in Anagni.[59] Afterwards, a new pope faithful to the French was elected, and the papacy was briefly relocated to Avignon (1309–1377).[63] During this period Rome was neglected, until a plebeian man, Cola di Rienzo, came to power.[63] An idealist and a lover of ancient Rome, Cola dreamed about a rebirth of the Roman Empire: after assuming power with the title of Tribuno, his reforms were rejected by the populace.[63] Forced to flee, Cola returned as part of the entourage of Cardinal Albornoz, who was charged with restoring the Church's power in Italy.[63] Back in power for a short time, Cola was soon lynched by the populace, and Albornoz took possession of the city. In 1377, Rome became the seat of the papacy again under Gregory XI.[63] The return of the pope to Rome in that year unleashed the Western Schism (1377–1418), and for the next forty years, the city was affected by the divisions which rocked the Church.[63]

Early modern history

In 1418, the Council of Constance settled the Western Schism, and a Roman pope, Martin V, was elected.[63] This brought to Rome a century of internal peace, which marked the beginning of the Renaissance.[63] The ruling popes until the first half of the 16th century, from Nicholas V, founder of the Vatican Library, to Pius II, humanist and literate, from Sixtus IV, a warrior pope, to Alexander VI, immoral and nepotist, from Julius II, soldier and patron, to Leo X, who gave his name to this period ("the century of Leo X"), all devoted their energy to the greatness and the beauty of the Eternal City and to the patronage of the arts.[63]

During those years, the centre of the Italian Renaissance moved to Rome from Florence. Majestic works, as the new Saint Peter's Basilica, the Sistine Chapel and Ponte Sisto (the first bridge to be built across the Tiber since antiquity, although on Roman foundations) were created. To accomplish that, the Popes engaged the best artists of the time, including Michelangelo, Perugino, Raphael, Ghirlandaio, Luca Signorelli, Botticelli, and Cosimo Rosselli.

The period was also infamous for papal corruption, with many Popes fathering children, and engaging in nepotism and simony. The corruption of the Popes and the huge expenses for their building projects led, in part, to the Reformation and, in turn, the Counter-Reformation. Under extravagant and rich popes, Rome was transformed into a centre of art, poetry, music, literature, education and culture. Rome became able to compete with other major European cities of the time in terms of wealth, grandeur, the arts, learning and architecture.